The Galileo Problem

An analogy:

Galileo: the real world :: the average person today: academic literature

There’s a certain level of cognitive ability and effort needed to go from layman to domain expert where you can read a modern paper on quantum mechanics or chemistry or neuroscience. I believe a similar amount of cognitive ability and effort was needed back in the 1600s to (1) read everything that was known about the solar system and movements of heavenly bodies, (2) think about it, and then (3) go do your own experiments and discover new science.

That is, frankly, crazy.

The average scientific paper is as devoid of common sense and easily understandable knowledge as heliocentrism was to a common person in the 1600s. Granted, today’s scientific papers aren’t intended for a general audience. We have popular science journalism to fill the gap, but the gap is so large. And more importantly the pedagogical gap is enormous. Knowing a bit about a topic is nice, but learning deeply about it in order to one day contribute new knowledge is very different. This is the difference between cursory entertaining knowledge and knowledge that lets you control your livelihood.

It’s no surprise that science innovation has slowed down. Reaching the frontier of human knowledge takes a really really long time – a typical PhD takes 5-7 years of intensive study after completing an undergraduate degree, meaning someone might invest 9-11 years of higher education just to reach the boundary of what’s known in their narrow field. It also takes far too long to move from one place on that boundary to another. That’s why we hardly see the modern equivalent of a renaissance man - someone with broad depth and breadth of knowledge who’s able to contribute meaningfully to many research fields in a single lifetime. There’s far too much prior knowledge to be consumed.

It’s not that science teaching is worse than it once was necessarily. It’s simply become a major bottleneck to get thinkers the knowledge they need to discover new things. The total body of knowledge and discoveries has grown exponentially while the efficiency of learning has not.

I believe AI tools will play a major role in changing that. LLMs can answer custom questions with amazing ability. They’re a big step forward toward the holy grail of technical education: a personal tutor that can increase a students’ learning efficacy by up to 2 sigma over that expected in a classroom setting . And yet, they are far from perfect. AI can’t motivate a learner to be intrinsically interested in a topic, a limitation that’s been true for every technological advance in teaching .

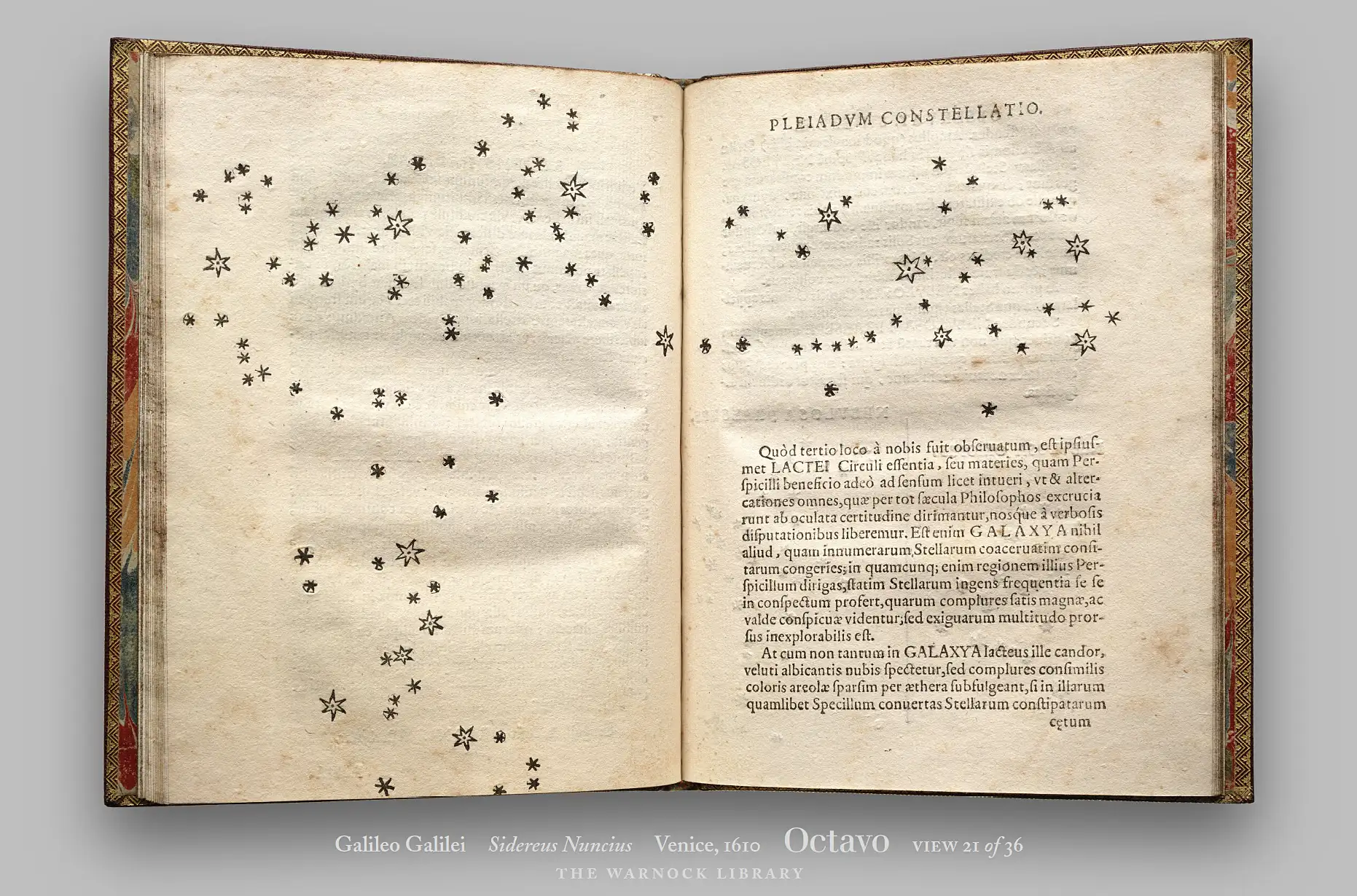

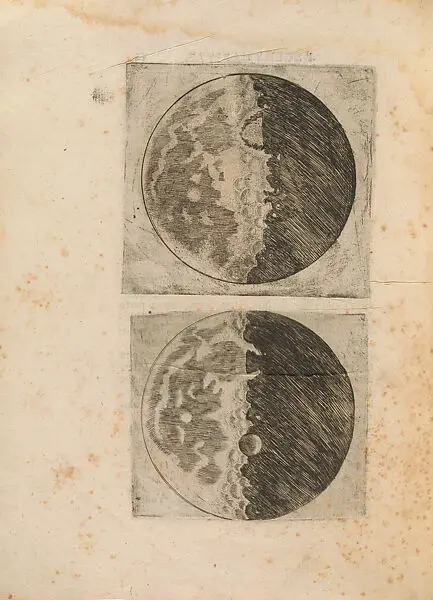

Making learning efficient is just one side of the coin. Today’s research isn’t motivated by gazing up at the proverbial heavens and asking ‘what’s out there’ as Galileo may have. Making learning desirable is the other major challenge. When faced with possibly contrived, unapparent, or highly technical research questions in modern science, discovering the ethos to push them forward is a non-trivial task. It requires compelling stories (fiction, non-fiction), compelling protagonists (scientists, science communicators, technology users), and the illustration of scientific mysteries often deeply hidden. It requires peeling back the curtain with a skilled poetic, and dramatic gesture. To show science with all the mythos and drama it’s never lost and always deserved.

Who, I say, does not know that all these emanate from the most benign star of Jupiter, after God the source of all good? It was Jupiter, I say, who at Your Highness’ birth, having already passed through the murky vapors of the horizon, and occupying the midheaven and illuminating the eastern angle from his royal house, looked down upon Your most fortunate birth from that sublime throne and poured out all his splendor and grandeur into the most pure air, so that with its first breath Your tender little body and Your soul, already decorated by God with noble ornaments, could drink in this universal power and authority.

Venice, 1610

Galileo Galilei